what teachers need to know about their students brains

Contempo inquiry on improving cognitive abilities of autistic children has shed new light on development of "normal" children's brains and has profound implications for improving education at all grade levels for all types of students.

A sweeping statement, I know, but one that is warranted past the exciting results.

I'll summarize the results of the new research, outline the implications, explain the neuroscience underlying the cognitive improvements, then conclude with specific recommendations for getting better results in the classroom.

Multi-sensory and motor enrichment in autistic children

Hither's what Cynthia Woo and colleagues of the Neurobiology and Behavior Section at UC Irvine found last year and why information technology's so of import.

Building on a wealth of animal enquiry showing that enriched sensorimotor experiences early in life significantly improve brain development and cognitive abilities, Woo's team compared IQ scores of autistic children ages 3-half dozen who either had standard care or half-dozen months of enriched sensorimotor experience.

Sensorimotor enrichment included activities such equally

- Scented bath and massage with oil

- Walking on foam pad or pillow

- Smelling different pairs of scents among a selection of lemon, lavender, vanilla, anise, orange, apple tree, and hyacinth

- Drawing shapes, tracking moving colored objects

- Viewing paired images and sounds

In all, children in the enriched group received 37 different sensorimotor stimuli over 6 months, including extensive movement and multi-sensory associations of bear on, temperature, odor, sight, sound, proprioceptive feedback, vestibular stimulating activities and social interaction.

The result? On average, kids in the enriched group raised their IQ scores 7 points relative to those in a standard intendance control grouping. More chiefly, 20% of children in the enriched protocol improved enough to motility out of the "autistic" classification, while none of the standard care group changed classification.

Broader implications of sensorimotor stimulation

The dramatic comeback resulting from sensorimotor enrichment is significant on many levels.

First, improvements in IQ occurred even though goose egg was explicitly taught to the children.

This finding adds to a fast growing trunk of data showing that activities that mostly strengthen the encephalon as a whole, rather than developing a specific part of the brain (eastward.g. localized brain regions for music, spoken linguistic communication, written language or motor coordination), are beneficial to a broad range of specific skills such as reading, quantitative skills and spatial skills measured on IQ tests.

Simply put, when it comes to encephalon function, "a rising tide lifts all boats."

Second, although Woo's research focused on autistic children, it's highly relevant to "normal" children because:

- The principal machinery past which sensorimotor enrichment enhanced brain function in autistic children-- formation of novel synaptic connections (e.m. with pairing of novel combinations of smells, sights, sounds and motility)—has also been shown to heighten operation and memory in "normal" brains, including those of mature adults. These novel connections are created based on the well-established principle of brain plasticity that "neurons that burn down together, wire together." Thus, when a developing brain is presented with novel combinations of smell, sight, bear on and sight, a new network is formed of neural pathways carrying signals in each of those sensory pathways. The greater the number of sensory channels stimulated, the more complex and rich the new neural network.

- Woo'due south research reinforces recent research showing that multi-modal (simultaneous activation of multiple sensory and motor pathways) is an effective manner to strengthen and literally "grow" the encephalon (e.g. children who feel coordinated sights, sounds and motor stimulation of playing a musical instrument have larger than normal regions of temporal cortex, the brain region that procedure music, and larger than normal representation of the fingers that play the instrument in their somatosensory cortex, the encephalon region that processes tactile information).

Finally—and perhaps well-nigh of import for education-- the amazing ability of sensorimotor stimulation has too been recently shown to improve the teaching of math and spelling skills in "normal" children.

Writing the Journal Pediatrics this year, Marijke J. Mullender-Wijnsma and colleagues of Groningen Academy in kingdom of the netherlands directed 2nd and 3rd class students to physically human action-out arithmetics and spelling lessons.

"The specific exercises were performed when the children solved an academic task. For example, the word 'dog' must be spelled by jumping in identify for every mentioned alphabetic character or the children had to jump half-dozen times to solve the multiplication '2x3'."

After two years, of such "embodied learning" exercises, students advanced their spelling and arithmetic skills by 4 full months over a matched control group.

And embodied learning works for much older students as well. University of Chicago researchers showed that college students studying physics who physically experienced the concept of angular momentum by holding spinning vs. stationary bicycle wheels, scored significantly higher on later quiz's almost the subject than students who learned about angular momentum through conventional "passive" techniques.

Hither's an everyday instance of embodied learning that you can relate to. Notice that when you are a rider being driven by someone else to a new location, it'southward much harder to remember the new route than when you are the driver.

The neuroscience of knowledge and learning

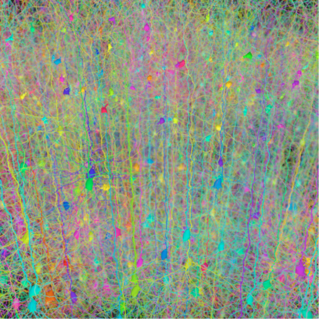

The prototype below is a model of human cerebral cortex showing a dumbo network pyramidal nervus cells and their dendrites (the neuronal fibers that receive inputs from other neurons). Pyramidal cells in the cortex –which practice a lot of the "heavy lifting" of sensing, thinking and behaving, take elaborate dendritic "copse" (colored fibers) that receive inputs from sensory relays such equally the Thalamus buried deep in the brain and from other parts of the cerebral cortex.

Source: Hermann Cuntz/PLOS Computational Biology.

Through these diverse inputs, individual neurons can be turned on (or off) past multiple sensory channels, such as vision, touch on and acoustic signals, equally well as by inputs from nerve cells in motor cortex that command our muscles to motility. In this image, nerve cells receiving inputs from unlike sensory and motor channels are depicted in different colors (turquoise for vision, blue for audition, green for both vision and audition, etc.), underscoring the multi-sensory nature of this department of cerebral cortex.

Taken together, cortical neurons and synapses (connections) between neurons course a vast neural network that perceives, decides, judges, imagines, learns and acts. The bigger and more richly interconnected the network, the more capable the network is.

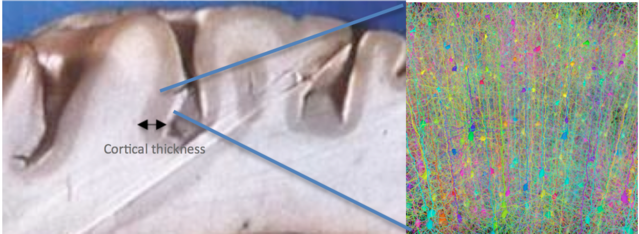

For case, recent research has shown that people with higher up average intelligence have a thicker than normal cerebral cortex like that shown below, containing bigger neurons with larger numbers of interconnections. Especially pregnant are generalized thickenings in and then-called "association" areas of the brain where multiple senses and motor channels come together.

Source: Eric Haseltine/Hermann Cuntz

Fortunately, information technology turns out that the size and richness of such neural networks tin be increased through mental exercise and learning. Such enhancement of cortical neural networks is exactly what happened with Woo'south autistic children, and with the embodied learning students in the Netherlands: the simultaneous use of multiple senses forth with motor involvement improved both general cerebral skills and learning of arithmetic and spelling.

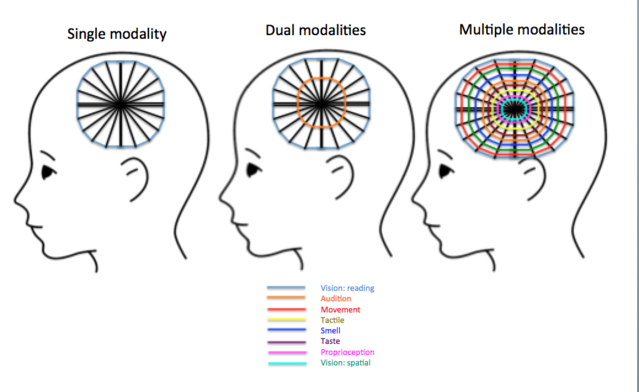

The graphic below depicts a elementary way of thinking about sensorimotor enrichment in the classroom.

Source: Eric Haseltine/Kopfproportionen

Retrieve of the neural networks inside a student's brain as a web. Every student has a bones matrix of neural connectivity, shown as the "spokes" of the web. As novel connections are formed amid unlike sensory and motor pathways, a new "band" is added and the web thickens and becomes denser.

When new information is presented to a child'south brain through a unmarried sensory channel, such equally reading, a simple neural network of synaptic connections is enhanced, shown on the far left. Synchronizing visual and auditory data, as occurs with multimedia presentations, adds another "ring" to the web. Finally, incorporating motor behavior and other senses, including bear on, smell, taste and proprioceptive (feedback on limb and head and heart position), the neural net "spider web" grows very dumbo.

Now imagine that when yous teach a student, you are attempting to "throw" new ideas, concepts and information at a web in their brain. The denser the web, the greater likelihood that the lesson you are instruction volition be "defenseless " and will "stick" in the educatee's encephalon.

I caveat: multi-sensory presentations and motor involvement during learning must exist carefully coordinated, synchronized and integrated with the task at hand. For instance, having a student perform random physical exercise while learning, might really distract the child past increasing what homo factors specialists call "chore loading."

And motor behavior needs to "fit" the lesson, as when students jump upwards and downwardly to demonstrate the addition of two numbers.

Similarly, it is important to avoid sensory overload when presenting information through multiple sensory channels: sights, sounds and tactile sensations must synch up in a natural way and "belong together," as when a child holds pet that presents natural sights, sounds, odors and feels furry to the child.

Recommendations for teachers

The concepts of coordinated, synchronized sensorimotor stimulation and embodied learning suggest that:

- Whenever possible—and within the constraints of keeping classes "nether control"—students should physically act out lessons. An added do good of such physical activeness is increased blood flow to the encephalon, which, by itself, improves learning and general cognitive abilities. In other words, radically redefine "physical pedagogy" moving concrete activity from the playground into the classroom

- Add together tactile stimulation, smells and tastes to lesson plans. If possible, go on calculation new sights, sounds, tastes and smells, because novel stimuli form novel, denser connections. The encephalon craves novelty!!

- Have students take new seats every week: sitting in novel locations, with dissimilar classmates to interact with, will assist students' brains abound new synapses

All of this added multi-sensory and motor components of instruction will not merely improve learning and retention of specific lessons, only will also likely elevate general cognitive abilities in the same way that Woo'southward sensorimotor helped autistic children.

And changing things around all of the time in the classroom, experiencing new smells, tastes, sights and sounds and physically demonstrating what students should do, will grow healthy neural nets in teachers' brains every bit well as those of their students. Inquiry has shown that such strengthening of "neurological reserves" delays or even preclude cognitive turn down with age.

Recall, when information technology comes to brain part, a ascent tide lifts all boats!

- Marijke J Mullender-Wijnsma,, Moderate-to-vigorous physically active academic lessons and academic appointment in children with and without a social disadvantage: a inside bailiwick experimental design, BMC Public Wellness. 2015; xv: 404.

- http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early on/2016/02/22/peds.201…

- Ratey, J.,SPARK: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the BrainLittle, Brown and Visitor (January ten, 2008)]

- https://world wide web.psychologytoday.com/web log/ulterior-motives/201507/how-does-p…

- https://hpl.uchicago.edu/sites/hpl.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/Kontra%20…

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18805039

- http://faculty.ucr.edu/~aseitz/pubs/Shams_Seitz08.pdf

- http://www.table salt-box.co.uk/uploads/ane/0/i/9/10196192/72_ways_to_make_lear…

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/radical-teaching/201609/memorizing…

- http://pact.cs.cmu.edu/pubs/koedinger,%20Kim,%20Jia,%20McLaughlin,%20Bi…

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/web log/ulterior-motives/201507/how-does-p…

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2996135/

- http://neuroscience.uth.tmc.edu/s4/chapter07.html

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3858645/

- Woo, Cynthia C.; Donnelly, Joseph H.; Steinberg-Epstein, Robin; Leon, Michael (Aug 2015). "Environmental enrichment equally a therapy for autism: A clinical trial replication and extension". Behavioral Neuroscience. 129 (4): 412–422.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/manufactures/PMC2678742/

- Karama S, et al, Positive clan between cerebral power and cortical thickness in a representative U.s.a. sample of healthy 6 to 18 year-oldsIntelligence. 2009 Mar; 37(ii): 145–155.

- Roberto Coloma, et al Distributed encephalon sites for the yard-factor of intelligence

- Volume 31, Issue 3, 1 July 2006, Pages 1359–1365

- Lawrence Katz, Keep Your Brain Alive: 83 Neurobic Exercises to Help Preclude Retention Loss and Increment Mental Fitness Kindle Edition

- T. P. Doubell and One thousand. G. Stewart, Brusque-Term Changes in the Numerical Density of Synapses in the Intermediate and Medial Hyperstriatum Ventrale following One-Trial Passive Avoidance Training in the Chick, Trends Neurosci. 2011 Apr; 34(4): 177–187.

- Min Fu and Yi Zuo, Experience-dependent Structural Plasticity in the Cortex, Trends Neurosci. 2011 Apr; 34(4): 177–187.

- Henriette van Praag, Gerd Kempermann and Fred H. GageNEURAL CONSEQUENCES OF ENVIRONMENTAL ENRICHMENT NATURE REVIEWS | NEUROSCIENCE Volume 1 | DECEMBER 2000 | 191

Source: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/long-fuse-big-bang/201609/what-teachers-need-know-about-their-students-brains

0 Response to "what teachers need to know about their students brains"

Post a Comment